Most people who get infected with tuberculosis never get sick. That’s not a myth-it’s science. The bacteria that cause TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can live quietly in your lungs for years, even decades, without causing a single symptom. But if your immune system weakens, those same bacteria can wake up, multiply, and turn into a life-threatening illness. This is the quiet danger of tuberculosis: two states, one pathogen, vastly different outcomes.

Latent TB: The Silent Carrier

Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) means you have the bacteria in your body, but your immune system has locked them down. You don’t feel sick. You don’t cough. You can’t spread it to anyone. That’s why so many people live with it without knowing. A positive tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) is often the only clue. Your chest X-ray looks normal. Your sputum is clean. Everything seems fine.But here’s the catch: about 5 to 10% of people with latent TB will eventually develop active disease in their lifetime. That risk jumps to over 50% if you have untreated HIV, are on immunosuppressants, or have diabetes or kidney failure. The bacteria aren’t gone-they’re just waiting. Granulomas, small clusters of immune cells, surround the bacteria and keep them in check. But if those walls crack, the infection breaks loose.

Latent TB isn’t just a medical curiosity. It’s the biggest reservoir for future TB cases. In the U.S., an estimated 13 million people have latent TB. Globally, it’s nearly 2 billion. That’s why public health programs focus so hard on finding and treating latent infections in high-risk groups-immigrants from high-burden countries, healthcare workers, people in homeless shelters, and those with weakened immune systems.

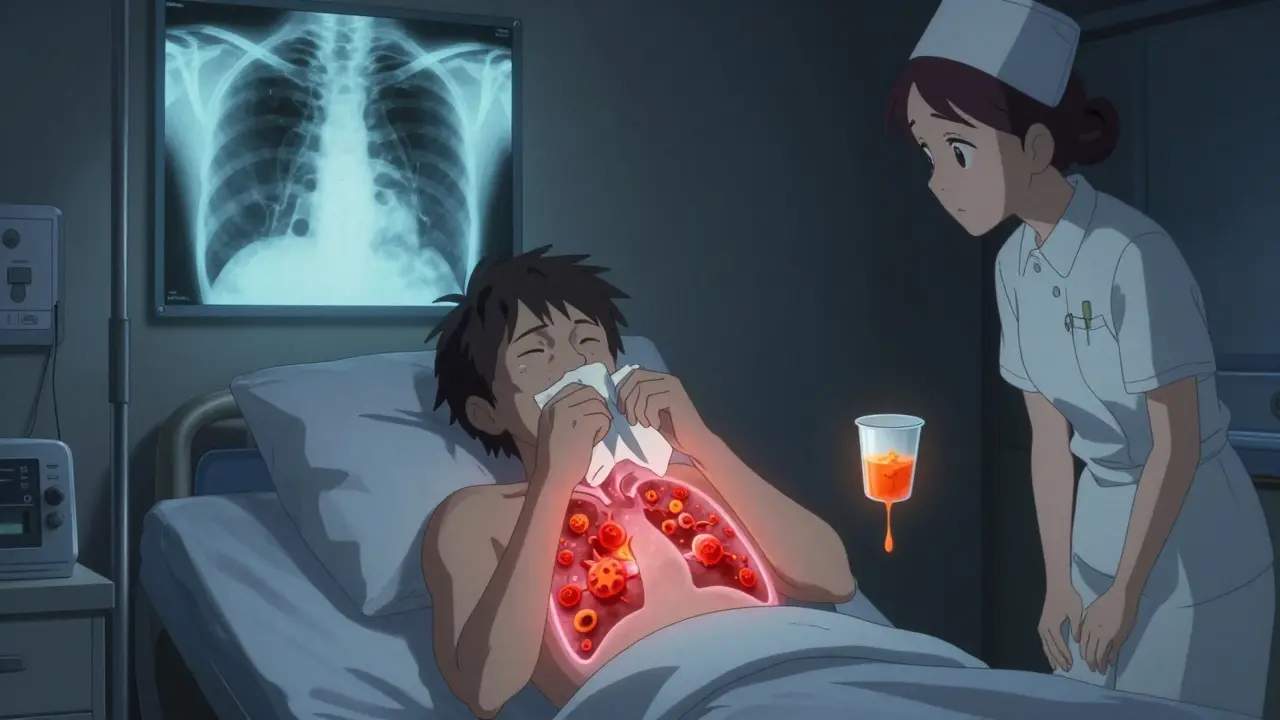

Active TB: When the Bacteria Fight Back

Active tuberculosis is when the bacteria break free from their prison and start multiplying. They attack lung tissue, cause inflammation, and trigger the classic symptoms: a cough that lasts more than three weeks, night sweats so heavy you change your pajamas, unexplained weight loss, fever that comes and goes, and extreme fatigue. Some people cough up blood. Others feel chest pain when they breathe or laugh.These symptoms don’t show up overnight. They creep in over weeks or months. Many people ignore them at first, thinking it’s just a lingering cold or the flu. By the time they see a doctor, the infection has often spread. A chest X-ray will show shadows, cavities, or fluid in the lungs. Sputum tests will find live bacteria under the microscope or confirm their DNA through nucleic acid amplification tests.

And here’s the critical part: if you have active TB in your lungs, you can spread it. Every cough, sneeze, or even loud conversation releases tiny droplets into the air. Someone breathing those droplets can get infected. That’s why active TB is treated as a medical emergency-not just for the patient’s sake, but for everyone around them.

How TB Is Diagnosed: Tests That Make the Difference

Diagnosing TB isn’t one test-it’s a puzzle. For latent TB, doctors rely on two blood or skin tests: the IGRA or TST. Both detect your immune system’s memory of the bacteria. A positive result doesn’t mean you’re sick-it means you’ve been exposed. That’s why a normal chest X-ray and no symptoms are required to confirm latent infection.For active TB, things get more urgent. A chest X-ray is the first step. If it looks suspicious, sputum samples are collected-usually three morning samples over different days. Lab technicians look for the bacteria under a microscope and grow them in culture, which takes weeks. Faster tests, like the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay, can detect TB DNA and check for resistance to rifampin in under two hours. That’s a game-changer for starting the right treatment quickly.

People with HIV or other immune problems may not show typical symptoms. Their chest X-rays might look normal, or their sputum tests negative, even when TB is spreading. That’s why doctors often use a combination of tests and clinical judgment, not just lab results, to make the call.

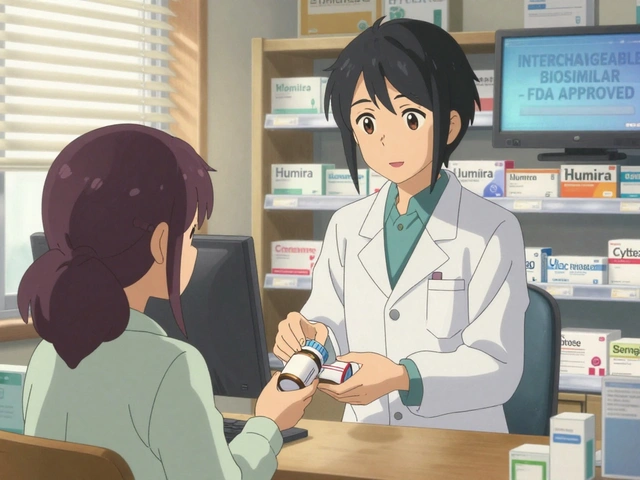

Drug Therapy for Latent TB: Preventing the Next Outbreak

Treating latent TB isn’t about curing symptoms-it’s about stopping future disease. The goal is simple: kill the dormant bacteria before they wake up. The gold standard has been nine months of daily isoniazid. It works, but it’s hard to stick with. Missing doses increases the risk of drug resistance.Thankfully, shorter regimens are now preferred. The CDC and WHO recommend a 3-month course of weekly isoniazid and rifapentine, taken under direct observation. Another option is four months of daily rifampin. Both are more effective at getting people to finish treatment. One study showed completion rates jumped from 60% with nine months of isoniazid to over 85% with the three-month combo.

Not everyone needs treatment. Healthy adults with low risk of progression might be monitored instead. But for people with HIV, recent TB exposure, or organ transplants, treatment is non-negotiable. Side effects like liver damage are rare but real. That’s why doctors check liver enzymes before and during treatment. No one wants to trade one health problem for another.

Drug Therapy for Active TB: The Four-Drug Battle

Active TB doesn’t wait. It needs a strong, fast response. The standard treatment starts with four antibiotics: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. This combo attacks the bacteria in different ways, reducing the chance of resistance. This intensive phase lasts two months.After that, you switch to two drugs-isoniazid and rifampin-for another four to seven months. Total treatment? Six to nine months. That’s a long time. Many patients feel better after a few weeks and stop taking pills. That’s how drug-resistant TB is born.

That’s why directly observed therapy (DOT) is standard. A nurse or community health worker watches you swallow every pill. It’s not about distrust-it’s about survival. In places like New York City and Atlanta, DOT programs have cut treatment failure rates by half. The CDC insists on it for all active TB cases.

Side effects are common. Rifampin turns your urine orange. Pyrazinamide can cause joint pain. Isoniazid can damage your liver. Regular blood tests are part of the routine. If you develop nausea, yellow skin, or dark urine, call your doctor immediately. Most side effects are manageable, but ignoring them can be deadly.

Drug Resistance: The Growing Threat

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) means the bacteria no longer respond to the two strongest drugs: isoniazid and rifampin. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) adds resistance to even more drugs. These strains are harder to treat, take up to two years to cure, and cost 100 times more than standard therapy.MDR-TB isn’t rare. The WHO estimates 450,000 new cases each year. Most come from people who didn’t finish their treatment or were given the wrong drugs. It’s not magic-it’s math. Every missed pill gives the bacteria a chance to mutate. That’s why adherence isn’t just important-it’s the difference between life and death, for you and your community.

New drugs like bedaquiline and delamanid are helping, but they’re not widely available everywhere. The real solution? Faster diagnosis, better treatment adherence, and more investment in public health systems that don’t wait for outbreaks to respond.

Who’s at Risk-and Why It Matters

TB doesn’t pick sides. But it does pick populations. In the U.S., over 70% of cases occur in people born outside the country, especially from India, China, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Nigeria. Among U.S.-born people, rates are highest in Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous communities. Why? Crowded housing, limited access to care, language barriers, and stigma keep TB hidden.HIV co-infection is the deadliest combo. Someone with untreated HIV and latent TB has a 10% chance of developing active TB each year-not over their lifetime, but every year. That’s why testing for both is routine in clinics that serve high-risk groups.

Healthcare workers, prison inmates, and people in homeless shelters are also at higher risk. These aren’t abstract groups-they’re neighbors, coworkers, family members. TB spreads where people live, work, and gather. That’s why screening programs in shelters and clinics aren’t optional. They’re essential.

What You Can Do

If you’ve been exposed to someone with active TB, get tested. If you’re from a country where TB is common, get tested even if you feel fine. If you have HIV or take immune-suppressing drugs, ask your doctor about latent TB screening. It’s quick, cheap, and life-saving.If you’re diagnosed with latent TB, finish your treatment-even if you feel fine. If you have active TB, take every pill, every day, and let someone watch you take it. Don’t hide it. Don’t delay. TB is treatable. But only if you act.

The fight against TB isn’t over. It’s just changing. We have the tools. We know how to stop it. What’s missing is the will to use them-on everyone, everywhere, before it’s too late.

Comments

Ambrose Curtis

man i had no idea latent tb was so common. my grandma had it back in the 80s and they just told her to take pills for a year. she never even told us until she was dying of liver issues from the meds. why dont more people know this stuff?

Amber Daugs

People still don't take this seriously enough. It's not just some "old person disease"-it's a silent epidemic hiding in plain sight. If you're from a high-risk country and you're asymptomatic, you're a walking time bomb. Stop pretending it's not your problem.

Linda O'neil

if you're reading this and you've been told you have latent tb-don't panic. just do the treatment. it's not a life sentence, it's a life saver. i know it's a long haul but your future self will thank you. you got this.

Robert Cardoso

the entire public health approach to tb is a failure of statistics over humanity. they test immigrants like they're suspects, ignore the homeless, and act surprised when outbreaks happen. it's not about bacteria-it's about who gets to be seen as worthy of care.

Kevin Kennett

my cousin was a nurse in a shelter in chicago. she saw tb cases go from 3 a year to 17 in 18 months. no one was testing anyone until someone coughed blood in the waiting room. we need screening everywhere-not just in clinics. shelters, jails, even food banks. this isn't optional.

Rose Palmer

It is imperative to underscore that adherence to the full course of treatment remains the single most effective intervention in curtailing the transmission of both latent and active tuberculosis. Failure to comply directly contributes to the proliferation of multidrug-resistant strains, which pose an existential threat to global health infrastructure.

Mindee Coulter

tb is not a choice but a reality. if you feel fine dont ignore the test. your silence hurts others

Bryan Fracchia

we treat tb like a medical problem when it's really a social one. the bacteria don't care about borders or income. they only care about crowding, stress, and neglect. until we fix housing, healthcare access, and stigma, we're just playing whack-a-mole with a virus that's already won.

Timothy Davis

you people act like isoniazid is poison. it's been used since the 50s. the real problem is people who think they're too healthy to need treatment. you're not special. your immune system isn't invincible. stop being a statistic waiting to happen.

Brittany Fiddes

in the UK we don't have this problem because we have a proper NHS. you americans think healthcare is a privilege, not a right. that's why tb thrives. your system is broken and you're too proud to admit it.

Colin Pierce

my brother did the 3-month rifapentine thing. it was easy. took it with his morning coffee. no more liver checks, no daily pills. just one pill a week for 12 weeks. i wish more people knew this was an option. it's not a punishment-it's a gift.

Jeffrey Carroll

While I appreciate the thoroughness of the post, I must emphasize that the ethical implications of mandatory DOT programs warrant deeper societal reflection. Autonomy versus public safety is not a binary choice-it is a spectrum requiring nuanced policy design.

James Dwyer

you're not alone. i had latent tb. took the 3-month combo. felt weird at first but now i'm fine. if you're scared, talk to someone. don't suffer in silence. we've all been there.