Every time a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic, they’re making a decision with real legal consequences. It’s not just about saving money-it’s about who bears the risk if something goes wrong. In 2026, with over 90% of prescriptions filled as generics, this isn’t a rare edge case. It’s daily practice. And the law hasn’t kept up.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t as Simple as It Looks

Generic drugs are cheaper because they don’t repeat the expensive clinical trials brand-name companies run. But they still have to prove they’re bioequivalent-meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at a similar rate. The FDA requires this range: 80% to 125% of the brand’s levels. Sounds precise, right? Not always. For drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure medications, even small differences in absorption can cause big problems. A 2017 study in Epilepsy & Behavior found that nearly 1 in 5 patients had therapeutic failure after switching to a generic antiepileptic. That’s not a fluke. It’s a pattern. And when patients have seizures, hospitalizations, or neurological damage because of it, someone gets sued. Here’s the catch: under the 2011 Supreme Court case PLIVA v. Mensing, generic manufacturers can’t be held liable in state court for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to use the exact same label as the brand-name drug. They can’t change it-even if new safety data emerges. So if a patient is harmed, the legal door is shut on the maker of the generic drug. That leaves the pharmacist, the prescriber, or the patient with nowhere to turn.State Laws Are a Patchwork-And That’s Dangerous

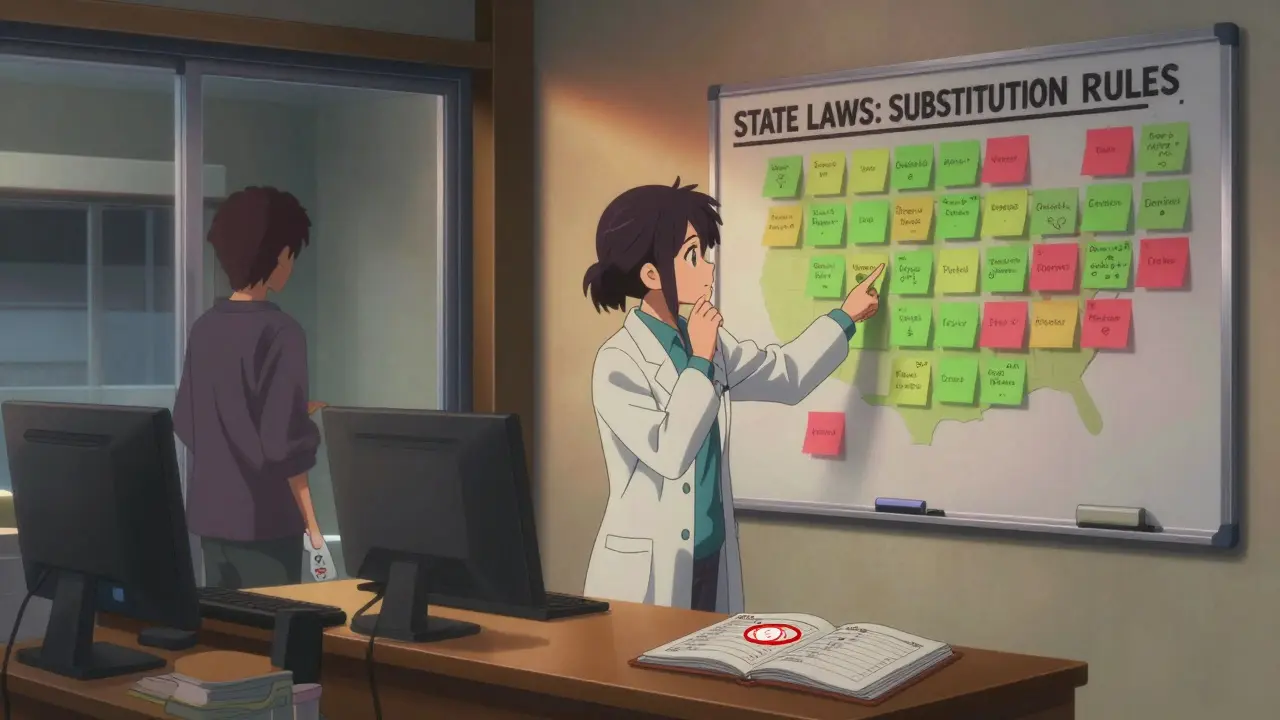

There’s no national rulebook for generic substitution. Each state sets its own rules, and the differences matter a lot.- 27 states require substitution unless the doctor or patient says no.

- 23 states let pharmacists substitute, but don’t force them to.

- Only 18 states require the pharmacist to directly notify the patient-beyond just the label.

- 32 states let patients refuse substitution.

- 27 states protect pharmacists from being held more liable for dispensing a generic than a brand-name drug.

- 23 states? No such protection. In Connecticut, for example, pharmacists could be sued more easily if they substitute.

Who’s at Risk-and Who’s Not

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to substitution risk.- Low risk: Statins, metformin, lisinopril. These have wide therapeutic windows. Even if absorption varies a little, it rarely causes harm. Most patients tolerate generics here without issue.

- High risk: Warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, carbamazepine, cyclosporine. These have narrow therapeutic indices. Blood levels need to be exact. A 10% change in absorption can mean the difference between control and crisis.

How Pharmacists Can Protect Themselves

You can’t control federal preemption. But you can control what happens in your pharmacy. Here’s what works:- Know your state’s law. Don’t guess. Check the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s annual compendium. Laws change. Last year, New York updated its consent rules. This year, California’s SB 452 could require shared liability.

- Flag high-risk drugs in your system. Set up electronic alerts in your pharmacy software for levothyroxine, warfarin, antiepileptics. If a generic is selected, the system should prompt you to pause and verify.

- Get documented consent. Even if your state doesn’t require it, use a simple form: “I understand my medication has been changed from [Brand] to [Generic]. I’ve been told the risks. I agree to this substitution.” Have the patient sign it. Keep it in their file.

- Communicate with prescribers. If a patient has had issues before, call the doctor. Ask: “Would you like me to dispense the brand?” Most will say yes. And if they don’t? Document that conversation.

- Log every substitution. Record the generic manufacturer, lot number, and date. If a problem arises later, you’ll need to trace it. This isn’t just good practice-it’s your legal shield.

- Get extra insurance. Standard malpractice policies often exclude substitution-related claims. Ask your insurer about supplemental coverage. It costs $300-$500/year. Worth it.

What’s Changing-and What’s Coming

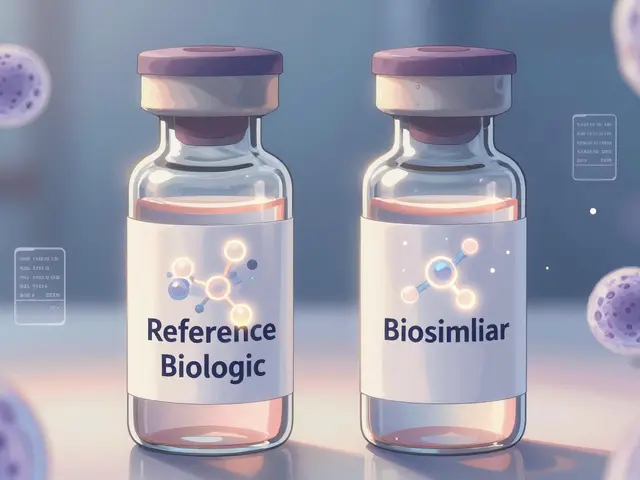

The system is cracking under pressure. In 2023, 11 states introduced bills to fix the liability gap. California’s SB 452 would require brand-name manufacturers to update labels within 30 days of new safety data-and force generics to adopt those updates within 60 days. That’s a big shift. If it passes, it could finally close the loophole that lets generic makers ignore new risks. The FDA is also testing a pilot program to let generic manufacturers request label changes. So far, only 12% of requests came from them. Most came from prescribers or patients. That tells you something: the system isn’t designed to catch problems early. Biosimilars are next. These are complex biologic drugs-like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis treatments-that now have generic-like versions. Forty-five states already have substitution laws for them. But their chemistry is far more complex than pills. One batch can vary more than another. Liability for biosimilars? Still undefined.The Bottom Line: It’s Not About Cost Anymore

Yes, generics save the U.S. healthcare system $1.67 trillion a decade. That’s huge. But when patients lose their health because of a substitution they didn’t know about, the cost isn’t just financial. It’s human. Pharmacists aren’t just filling scripts. You’re the last line of defense. If you don’t question a substitution for warfarin or levothyroxine, you’re not being efficient-you’re being negligent. The law may protect manufacturers. But it doesn’t protect you. Not unless you act. Start with one thing today: check your state’s substitution law. Then, put a flag in your system for high-risk drugs. Document every swap. Talk to your patients. You don’t need a law degree to do that. You just need to care enough to do it right.Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes, depending on the state and circumstances. While federal law shields generic manufacturers from liability for labeling issues, pharmacists can still be held responsible if they fail to follow state substitution laws, don’t obtain required consent, or substitute a high-risk drug without proper safeguards. In states without liability protections, pharmacists may face malpractice claims if a patient is harmed after a substitution.

Which drugs are most dangerous to substitute?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index are the most dangerous to substitute because small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm. These include warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), phenytoin and carbamazepine (antiepileptics), and cyclosporine (immunosuppressant). Studies show higher rates of therapeutic failure and adverse events with generic versions of these drugs.

Do patients have the right to refuse a generic substitution?

Yes, in 32 states, patients have the legal right to refuse a generic substitution. Even in states where substitution is mandatory, patients can opt out. Pharmacists must inform patients of their right to refuse, and in 18 states, they’re required to do so directly-not just through labeling. Always confirm patient preference in writing.

Why can’t generic manufacturers update their drug labels?

Federal law requires generic manufacturers to use the exact same label as the brand-name drug. They cannot independently add or change warnings-even if new safety data emerges. This rule was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2011 (PLIVA v. Mensing) and reinforced in 2013 (Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett). The result: patients may be exposed to risks that the brand-name label doesn’t even warn about.

What should a pharmacist do if a patient reports side effects after a generic switch?

Immediately document the report, including the patient’s symptoms, the drug name, manufacturer, and lot number. Contact the prescribing provider to discuss whether to switch back to the brand or try another generic. Review your substitution log to confirm the change was documented and consent was obtained. If the patient is seriously affected, consider reporting the adverse event to the FDA’s MedWatch program. This isn’t just good care-it’s critical legal protection.

Is there a way to avoid liability entirely?

You can’t eliminate liability, but you can drastically reduce it. Follow your state’s laws exactly. Use electronic alerts for high-risk drugs. Get written consent. Maintain detailed substitution logs. Communicate with prescribers. Get supplemental malpractice insurance. Pharmacists who implement these steps see up to 64% fewer complaints. Risk isn’t about avoiding action-it’s about acting with intention and documentation.

Comments

Cassie Widders

Been a pharmacist for 18 years. The real issue isn't the law-it's the silence. Patients assume the pill in their hand is the same. They don't know the difference between a generic and the brand until they're dizzy, or seizing, or in the ER. I started using consent forms after a patient had a stroke from a warfarin switch. No one told her. Not the doctor. Not the system. Just me, holding a clipboard, asking her to sign. It felt awkward. Now it's routine. And I sleep better.

Ben Kono

Why are we even talking about this like it's a mystery The FDA lets generics be 20 percent off in absorption and we act surprised when people get sick This isn't a pharmacy problem it's a regulatory failure

Darryl Perry

Statistical outliers do not constitute systemic risk. The vast majority of generic substitutions occur without incident. Overregulating based on rare cases harms efficiency and increases costs for patients who rely on affordability. The system works. Fix what's broken, don't overcorrect.

Windie Wilson

Oh so now pharmacists are the new superheroes of the healthcare system? Let me guess-next you'll tell me we should make them carry defibrillators and write poetry for depressed patients. Meanwhile, the real culprits-pharma execs who lobby to keep labels frozen-are sipping champagne in their penthouses. But sure, let’s blame the person handing out the pills.

Rinky Tandon

Let me be unequivocal: the current regulatory architecture is a catastrophic failure of biomedical governance. The PLIVA v. Mensing doctrine represents a pernicious form of federal preemption that immunizes manufacturers from tort liability while externalizing risk onto frontline clinicians-this is not merely a legal anomaly, it is a structural epistemic injustice. Pharmacists are being coerced into de facto risk-bearing agents without commensurate autonomy or indemnity. The FDA’s passive stance on label harmonization constitutes a dereliction of its statutory duty under the FDCA. Until we institute mandatory bioequivalence thresholds for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs and enforce dynamic label alignment across originator and generic manufacturers, we are complicit in a system that commodifies patient safety. This is not pharmacology-it’s liability roulette.

Konika Choudhury

India has been doing generic substitution for 30 years and we have the safest drug supply in the world Why are Americans making such a big deal about this We produce 40 percent of the world’s generics and no one is dropping dead from levothyroxine

Daniel Pate

If liability is shifted to pharmacists because manufacturers can’t be held accountable, are we not essentially punishing the most vulnerable actors in the supply chain? Who benefits from this? The manufacturers. The insurers. The shareholders. Not the patient. Not the pharmacist. Not even the prescriber. This isn’t about law-it’s about power. Who gets to decide what risk is acceptable, and who gets to pay for it when it goes wrong? The answer is written in the fine print of a federal regulation that no one reads until someone dies.

Amanda Eichstaedt

My grandma switched to a generic levothyroxine and went from feeling fine to barely able to get out of bed. She didn’t know it changed. The pharmacist didn’t say a word. She thought it was the same pill. She’s fine now-back on the brand-but I’ll never forget how scared she looked. I’m not mad at the pharmacist. I’m mad at the system that lets this happen without a single conversation. Just… a pill. No warning. No choice. No care.