Hypokalemia Correction Calculator

Potassium Replacement Calculator

This tool helps determine appropriate potassium supplementation based on current potassium levels and diuretic use.

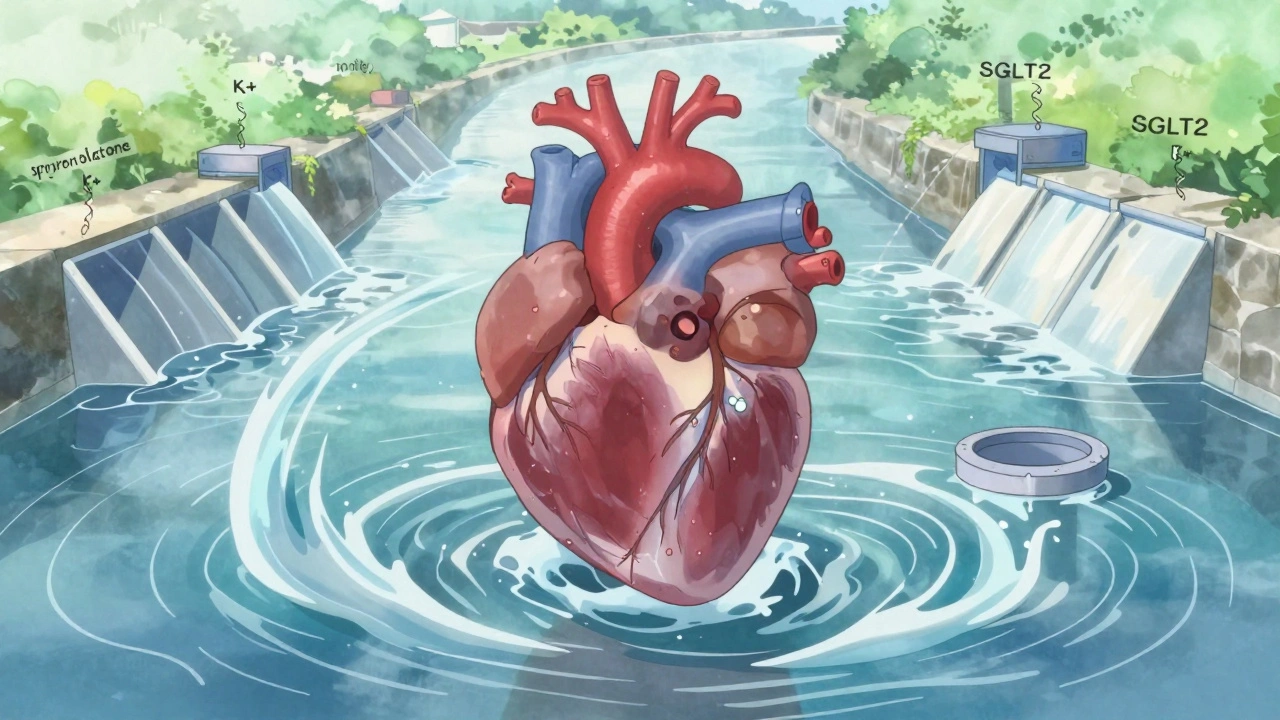

When you’re managing heart failure, diuretics are often the first line of defense against fluid buildup. But here’s the catch: the very drugs that help you breathe easier can also drop your potassium dangerously low. This isn’t just a side effect-it’s a silent threat that can trigger irregular heartbeats, hospital readmissions, or even sudden death. If you’re on furosemide, bumetanide, or torsemide, and your potassium level is below 3.5 mmol/L, you’re in a high-risk zone. And it’s more common than you think-about 1 in 4 heart failure patients on loop diuretics develop hypokalemia.

Why Diuretics Drain Potassium

Loop diuretics work by blocking salt reabsorption in the kidneys. That sounds good-less fluid, less swelling. But here’s what happens next: the extra salt that doesn’t get reabsorbed ends up in the distal part of the kidney, where it pulls potassium out with it. Think of it like a river carrying away more than just water-it’s sweeping potassium into your urine. The higher the dose, the worse it gets. And if you’re taking other meds like laxatives or steroids, or if you’ve been on a low-salt diet for too long, your body loses even more potassium.What’s worse, the body adapts. After a few days of diuretic use, your kidneys start holding onto sodium again. That’s called ‘within-dose tolerance.’ So you might need more diuretics just to get the same effect-and each extra dose means more potassium slipping away. This is why giving diuretics twice a day (like 20 mg of furosemide every 12 hours) works better than one big dose. It smooths out the peaks and valleys, giving your body less of a shock.

The Real Danger: Arrhythmias and Death

Low potassium doesn’t just make you feel tired or weak. In a heart already weakened by failure, it can cause ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation-deadly rhythms that stop the heart from pumping. Studies show that when potassium drops below 3.5 mmol/L, the risk of dying from heart failure jumps by 50% to 100%. That’s not a small number. It’s why guidelines from the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America say: monitor potassium like your life depends on it. And they do.The target range? 3.5 to 5.5 mmol/L. Not 4.0 to 5.0. Not ‘as close to normal as possible.’ Exactly 3.5 to 5.5. Anything below 3.5 is a red flag. Anything above 5.5 is also dangerous-but that’s a different problem. For now, focus on keeping it from falling.

How to Fix It: The Four-Step Plan

There’s no magic pill, but there’s a clear, evidence-backed plan. Here’s how to handle it:- Start with potassium supplements-if your level is between 3.0 and 3.5 mmol/L, give 20-40 mmol of oral potassium chloride daily. That’s usually two or three tablets. Don’t skip this. Many patients think ‘I’ll just eat more bananas.’ But you’d need 10 bananas a day to replace what a diuretic pulls out. It’s not practical.

- Add a potassium-sparing diuretic-this is the game-changer. Spironolactone (12.5-25 mg daily) or eplerenone (25 mg daily) blocks the hormone that makes your kidneys dump potassium. The RALES trial showed spironolactone cuts death risk by 30% in severe heart failure. That’s not just about potassium-it’s about survival. These drugs are now standard for anyone with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

- Check for hidden causes-are you taking laxatives? Are you vomiting? Are you on steroids? Did you stop your ACE inhibitor because your creatinine went up? These all make hypokalemia worse. Sometimes the fix isn’t more potassium-it’s stopping something else.

- Consider SGLT2 inhibitors-drugs like dapagliflozin and empagliflozin were originally for diabetes, but now they’re first-line for heart failure. They help you pee out fluid without losing potassium. In trials, they reduced the need for loop diuretics by 20-30%. That means less potassium loss overall. They also lower hospitalization rates. If you’re not on one, ask why.

When to Go to the Hospital

If your potassium is below 3.0 mmol/L, you need IV replacement-fast. Do not wait. This isn’t something you can fix with a pill at home. You’ll need to be monitored with an ECG because low potassium can cause dangerous rhythms. IV potassium is given slowly-no more than 10-20 mmol per hour-because too fast can stop your heart. And yes, you need to be in a hospital or monitored unit. No exceptions.Monitoring: When and How Often

Don’t wait until you feel bad. Check potassium:- At the start of any new diuretic or dose change

- Every week for the first month

- Then every month if stable

- Every 1-3 days if you’re hospitalized for worsening heart failure

And don’t forget to check kidney function at the same time. If your creatinine is rising, your kidneys aren’t handling the load. That changes everything.

What About Diet?

Yes, you should eat potassium-rich foods-sweet potatoes, spinach, beans, avocados, oranges. But don’t rely on them. A single banana has about 4.5 mmol of potassium. If you’re losing 20-40 mmol a day from diuretics, you’d need 5-9 bananas daily. That’s not realistic. Plus, many heart failure patients have kidney problems, and too much potassium can backfire. Balance is key. Focus on consistent, moderate intake-not extremes.

Special Cases: HFpEF vs. HFrEF

Not all heart failure is the same. If you have reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), you’re likely on MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors. That’s good-it protects your potassium. But if you have preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), you might not get those drugs. You might just get diuretics. That puts you at higher risk. Studies suggest aggressive diuresis in HFpEF doesn’t help much and might even hurt your kidneys. So if you have HFpEF, ask: Is this diuretic dose really necessary? Could we cut back?The Bigger Picture: Less Diuretic, Better Outcomes

The goal isn’t to make you lose every drop of fluid. It’s to make you feel better without breaking your electrolytes. The DOSE-AHF trial showed that if your kidney function dips during hospitalization, but you’re still peeing more and feeling less swollen, that’s actually a good sign. You’re responding. So don’t panic if your creatinine rises slightly. Focus on symptoms: Are you still short of breath? Are your ankles still swollen? If not, you might not need more diuretics.And here’s something new: extended-release diuretics are coming. These give a steadier effect, reducing those spikes in potassium loss. They’re not everywhere yet, but they’re on the horizon. Until then, splitting your dose twice a day is the next best thing.

What to Do Next

If you’re on diuretics and have heart failure:- Ask your doctor for your last potassium level-and when it was checked.

- Ask if you’re on a potassium-sparing diuretic. If not, why not?

- Ask if you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor. If not, are you a candidate?

- Don’t take over-the-counter laxatives or salt substitutes without talking to your doctor.

- Keep a log: weight daily, symptoms, and any muscle cramps or palpitations.

Heart failure management isn’t about one drug. It’s about the whole system. Diuretics are powerful, but they’re not the whole story. The best outcomes come when you combine them with MRAs, SGLT2 inhibitors, and careful monitoring. Don’t just treat the fluid. Treat the potassium. Treat the rhythm. Treat the whole person.

Can eating bananas fix hypokalemia caused by diuretics?

No. While bananas contain potassium, you’d need to eat 8-10 daily to replace what a typical diuretic dose removes. That’s not practical or safe for most heart failure patients, especially those with kidney issues. Oral potassium supplements are far more reliable and precisely dosed.

Is it safe to take potassium supplements with spironolactone?

It can be, but only under close medical supervision. Spironolactone reduces potassium loss, so adding supplements raises the risk of hyperkalemia (potassium too high). Your doctor will check your levels regularly and adjust doses accordingly. Never take extra potassium without a prescription.

Why do some heart failure patients need diuretics twice a day?

Loop diuretics like furosemide have a short duration of action. Giving them once a day causes large spikes in fluid and potassium loss, followed by rebound sodium retention. Splitting the dose (e.g., 20 mg every 12 hours) provides smoother, more consistent diuresis and reduces the risk of hypokalemia and diuretic resistance.

Can SGLT2 inhibitors replace diuretics in heart failure?

Not fully, but they reduce the need for them. SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin help remove fluid without draining potassium, lowering diuretic doses by 20-30% in trials. They’re now recommended as add-on therapy, not replacements. Most patients still need some diuretic, but often at a lower, safer dose.

What should I do if I miss a dose of my potassium supplement?

If you miss one dose, take it as soon as you remember-if it’s not close to your next dose. Don’t double up. If you miss multiple doses or start feeling weak, dizzy, or have palpitations, contact your doctor immediately. Low potassium can escalate quickly.

Comments

Christian Landry

This is so helpful 😊 I’ve been on furosemide for years and never knew splitting the dose made such a difference. My doc just gave me a 40mg daily and I thought that was it. Gonna ask about 20mg twice a day now.

Michael Robinson

It’s not just about potassium. It’s about listening to your body. When you’re tired and your heart feels like it’s skipping beats, that’s your body screaming. Don’t wait for the lab results.

Andrea DeWinter

If you're on a loop diuretic and not on an MRA or SGLT2i, you're missing half the treatment. These aren't add-ons-they're core. Ask your cardiologist why you're not on one. If they don't have a solid answer, get a second opinion.

Nikhil Pattni

I read this article and thought wow this is so basic but then I remembered most people don't even know what a loop diuretic is. Like seriously if you're on furosemide and your potassium is 3.2 you think eating a banana is enough? Bro that's like trying to fill a swimming pool with a teaspoon. You need meds not snacks. Also if you're on laxatives stop it. Like right now. Don't wait. Your colon is not your kidney.

Katie Harrison

I’ve been on spironolactone for 18 months now... and yes, it’s a game-changer. My potassium stayed stable, my swelling went down, and I actually slept through the night for the first time in years. But I do get cramps sometimes-so I still take a small supplement. Just not bananas. Never bananas again.

Kathy Haverly

They say monitor potassium like your life depends on it... but what if your doctor doesn’t? What if they’re just rushing you out the door? I had a potassium of 2.9 and they told me to ‘eat more oranges.’ I almost died. This isn’t advice-it’s negligence.

Mona Schmidt

The distinction between HFpEF and HFrEF is critical. Many clinicians still treat them the same, but the evidence is clear: aggressive diuresis in HFpEF offers no mortality benefit and increases renal risk. Patients with preserved EF need a different approach-less diuretics, more focus on comorbidities like hypertension and obesity.

William Umstattd

I can’t believe people still think bananas fix this. That’s like saying drinking water fixes dehydration after you’ve lost a liter of blood. This isn’t a nutrition blog-it’s a life-or-death medical protocol. If your doctor isn’t treating potassium like a critical vital sign, find a new one.

Arun Kumar Raut

I’m from India and we have a lot of heart failure patients here. Most don’t even know what potassium is. We need more education. Maybe community health workers can help explain this in simple terms. Not everyone has access to a cardiologist.

Chris Marel

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been scared to ask my doctor about my meds because I didn’t want to seem like I was questioning them. But now I know I should speak up. I’m going to ask about SGLT2 inhibitors next visit.

Haley P Law

I just got my potassium level back… 3.1. I’m crying. I’ve been eating 3 bananas a day and I thought that was enough. I feel so stupid. I’m going to the ER now.

Guylaine Lapointe

I read this and thought ‘finally someone gets it.’ But then I remembered half the cardiologists I’ve seen don’t even know what RALES is. They just say ‘take your pills’ and send you on your way. This isn’t medicine-it’s a checklist. You deserve better.

precious amzy

The entire paradigm of diuretic use in heart failure is built on flawed assumptions. The DOSE-AHF trial was funded by pharmaceutical interests. The real solution is not more drugs-it’s systemic change: reduce sodium, increase mindfulness, and restore natural homeostasis. Modern medicine has forgotten the body’s innate wisdom.

Carina M

It is imperative to underscore that the administration of potassium supplements in the context of loop diuretic therapy must be conducted under the strictest clinical supervision, as the potential for iatrogenic hyperkalemia-particularly in the presence of concomitant RAAS inhibition-constitutes a non-trivial, potentially fatal pharmacodynamic interaction.

Andrea Petrov

They say SGLT2 inhibitors reduce diuretic needs... but what if they’re just hiding the real problem? What if the real solution is to stop treating symptoms and start asking why we’re all so full of fluid in the first place? Maybe it’s the processed food. Maybe it’s the stress. Maybe it’s the government. You ever think about that?