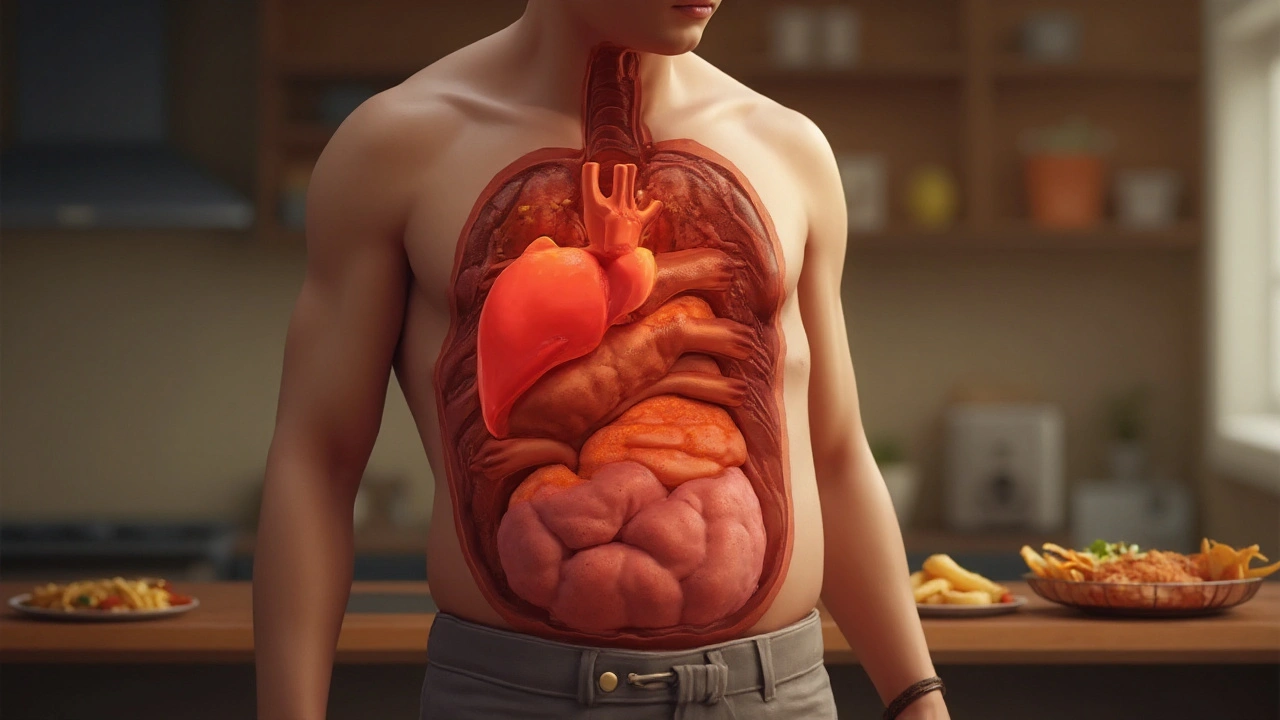

Left Ventricular Failure is a clinical syndrome where the left ventricle cannot pump blood effectively, causing reduced cardiac output and fluid buildup in the lungs and systemic circulation.

When doctors talk about heart failure, they often focus on the left side of the heart because it does most of the work delivering oxygen‑rich blood to the body. The connection between obesity and left ventricular failure (LVF) has moved from a curiosity to a central public‑health concern. In the UK, about 28% of adults are class‑III obese, and epidemiological data show that obese patients are up to three times more likely to develop LVF than their normal‑weight peers.

Why Obesity Matters for the Heart

Obesity is a chronic excess of adipose tissue, typically measured by a body‑mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m² or higher. The excess weight does more than just add a mechanical load; it triggers a cascade of metabolic, hormonal, and inflammatory changes that strain the left ventricle.

- Increased blood volume and cardiac output: Fat tissue is highly vascularized, so the heart must pump more blood to supply it.

- Elevated peripheral resistance: Obesity often co‑exists with hypertension, forcing the left ventricle to work against higher afterload.

- Neurohormonal activation: Levels of leptin, insulin, and angiotensin‑II rise, driving maladaptive remodeling.

- Systemic inflammation: Pro‑inflammatory cytokines (TNF‑α, IL‑6) promote fibrosis and stiffening of the myocardial wall.

Key Co‑morbidities that Amplify the Risk

Obesity rarely walks alone. Three conditions most frequently overlap and accelerate LVF.

Hypertension is a chronic elevation of arterial blood pressure, typically defined as systolic ≥140mmHg or diastolic ≥90mmHg. raises afterload, compelling the left ventricle to thicken (concentric hypertrophy) before it eventually dilates.

Diabetes Mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance or deficiency. fuels advanced glycation end‑products that stiffen myocardial collagen, impairing relaxation.

When these three sit together-obesity, hypertension, and diabetes-the heart faces a triple hit: volume overload, pressure overload, and metabolic toxicity.

Mechanistic Pathways Linking Fat and the Left Ventricle

The scientific community has identified several overlapping pathways.

- Neurohormonal overdrive: Adipose tissue releases leptin, which stimulates sympathetic activity, raising heart rate and contractility short‑term but causing burnout long‑term.

- Renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system (RAAS) activation: Obesity boosts renin secretion, leading to vasoconstriction and sodium retention, both of which increase ventricular wall stress.

- Inflammatory cascade: Elevated C‑reactive protein (CRP) and interleukins encourage myocardial fibrosis, reducing compliance.

- Metabolic derangements: Insulin resistance impairs glucose uptake in cardiomyocytes, shifting energy production toward fatty‑acid oxidation, which is less efficient and generates toxic intermediates.

These mechanisms converge on ventricular remodeling, a structural and functional change of the heart muscle in response to chronic stress. Over time, remodeling transitions from adaptive hypertrophy to maladaptive dilation and reduced ejection fraction (the percentage of blood the left ventricle pumps out with each beat)., the hallmark of LVF.

Clinical Picture: How Obesity‑Related LVF Differs

Patients with obesity‑driven LVF often present with a distinct phenotype compared with traditional ischemic heart failure.

| Feature | Obesity‑Related LVF | Non‑Obese LVF |

|---|---|---|

| Typical BMI | ≥30kg/m² | 18‑24kg/m² |

| Prevalence of Hypertension | ≈70% | ≈45% |

| Average Ejection Fraction | 35‑45% | ≤35% |

| Primary Driver | Volume overload + metabolic stress | Ischemia / myocardial infarction |

| 5‑Year Mortality | ≈30% | ≈40% |

Notice the higher ejection fraction range and lower mortality in the obesity group; this is sometimes termed "obesity paradox," where excess weight appears protective once heart failure is established. The paradox remains debated, but it underscores that management must be tailored.

Diagnosis: Spotting the Link Early

Early detection relies on a blend of clinical suspicion and targeted testing.

- History and physical exam: Look for BMI≥30, waist‑to‑hip ratio, and signs of fluid overload (pedal edema, jugular venous distention).

- Echocardiography: Provides EF, wall thickness, and diastolic function-key to differentiating concentric vs. eccentric remodeling.

- Biomarkers: Natriuretic peptides (BNP, NT‑proBNP) rise with ventricular strain; CRP and IL‑6 hint at inflammatory load.

- Metabolic panel: Fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid profile, and serum leptin help map the metabolic landscape.

Integrating these data points constructs a risk score that predicts progression to symptomatic LVF within 2‑3years for many obese patients.

Therapeutic Strategies: Beyond Weight Loss

Weight reduction is the cornerstone, but a multi‑pronged approach yields the best outcomes.

- Lifestyle modification: A calorie‑deficit diet (500‑750kcal/day) paired with aerobic exercise (150min/week) can drop BMI by 5‑7% in six months, improving EF by 3‑5 points on average.

- Pharmacotherapy:

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs blunt RAAS activation, lowering afterload.

- Beta‑blockers dampen sympathetic drive, reducing heart rate and oxygen demand.

- SGLT2 inhibitors, originally for diabetes, have shown a 25% reduction in heart‑failure hospitalizations even in non‑diabetic obese patients.

- Device therapy: In advanced cases, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) can improve coordination of ventricular contraction, especially when EF≤35%.

- Bariatric surgery: For BMI≥40 or ≥35 with comorbidities, sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass can reverse LV remodeling dramatically; studies report a 20‑30% increase in EF two years post‑surgery.

Crucially, each intervention should be personalized. A young, active professional may thrive on intensive lifestyle changes, while an older patient with multiple comorbidities might benefit more from early pharmacologic therapy and surgical weight loss.

Prevention: Keeping the Heart Healthy Before Failure Sets In

Public‑health initiatives and individual choices intersect.

- Screening: Routine BMI measurement at GP visits, coupled with blood pressure checks, can flag at‑risk individuals.

- Community programs: Walking groups, subsidised gym memberships, and nutrition workshops have reduced local obesity rates by up to 12% in pilot studies across England.

- Policy levers: Sugar‑taxes and clearer food‑labeling guidelines help curb excess calorie intake.

When these layers work together, the incidence of obesity‑driven LVF could drop significantly over the next decade.

Related Topics to Explore

Understanding the obesity‑LVF link opens doors to several adjacent concepts:

- Metabolic syndrome: The cluster of risk factors (abdominal obesity, high triglycerides, low HDL, hypertension, insulin resistance) that fuels cardiac stress.

- Adipokines: Hormones secreted by fat cells (leptin, adiponectin) that directly affect myocardial contractility.

- Cardiac MRI: Advanced imaging that quantifies fibrosis and helps differentiate obesity‑related remodeling from ischemic scar tissue.

- Exercise physiology: How aerobic vs. resistance training uniquely influences ventricular geometry.

Delving into these areas can deepen a clinician’s or patient’s grasp of the broader cardio‑metabolic picture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can losing weight reverse left ventricular failure?

Yes, modest weight loss (5‑10% of body weight) can improve ejection fraction, reduce wall stress, and lower hospitalisation risk. The effect is most pronounced when combined with guideline‑directed heart‑failure medication.

Why do some obese patients have a better prognosis after heart failure develops?

The so‑called “obesity paradox” may stem from higher metabolic reserves, different neurohormonal profiles, or earlier medical attention. However, it does not outweigh the long‑term risks of obesity, so weight management remains essential.

What role do SGLT2 inhibitors play in obese patients with heart failure?

SGLT2 inhibitors improve glycaemic control and promote natriuresis, lowering preload and afterload. Clinical trials show a 25% reduction in heart‑failure hospitalisation, even in non‑diabetic obese cohorts.

Is bariatric surgery recommended for patients with existing left ventricular failure?

For BMI≥35 with comorbidities, bariatric surgery is an evidence‑based option. Post‑operative studies report significant reductions in LV mass and improvements in EF, though patient selection and multidisciplinary follow‑up are crucial.

How often should an obese patient be screened for heart failure?

Annual cardiovascular review is advised for BMI≥30, especially if hypertension or diabetes are present. Echocardiography should be considered if symptoms (dyspnoea, fatigue) appear or if BNP levels rise.

Comments

Bansari Patel

Reading through the cascade of mechanisms really makes you stop and think about how the body tries to compensate until it simply can't. The increase in blood volume and peripheral resistance is like turning up the thermostat in a house that already feels too hot. Meanwhile, neurohormonal overdrive is the nervous system shouting "more work!" while the heart is already exhausted. Inflammation adds a sticky layer of fibrosis that limits the chamber’s flexibility – it’s a perfect storm. All these pieces together underline why we can’t ignore obesity as a mere cosmetic issue; it’s a systemic threat to cardiac health.

Understanding these pathways empowers clinicians to intervene earlier rather than waiting for overt failure.

Rebecca Fuentes

From a clinical perspective, the delineation between volume overload and pressure overload in obese patients is crucial. Echocardiographic assessment should therefore prioritize both ejection fraction and diastolic parameters to capture early remodeling. Additionally, biomarkers such as NT‑proBNP, when interpreted alongside inflammatory markers like CRP, can provide a more nuanced risk stratification. It is also advisable to incorporate routine BMI and waist‑to‑hip ratio measurements in annual cardiovascular reviews. These systematic approaches may help mitigate the progression toward overt left ventricular failure.

Jacqueline D Greenberg

Wow, this article really breaks down the whole "obesity paradox" thing. It's crazy how a little extra weight can actually give the heart a bit of a buffer, at least for a while. But the bottom line is still the same – losing those extra pounds can make a huge difference in how the heart works. I love the part about SGLT2 inhibitors helping even non‑diabetics – that's a game‑changer. If anyone's looking for something to start with, a simple calorie deficit and regular walks can move the needle fast. Keep sharing the good info!

Jim MacMillan

Honestly, the data on neurohormonal activation is nothing short of fascinating 😮💨. Leptin‑driven sympathetic overdrive is like the heart's version of a thermostat stuck on high – you keep turning up the output until the system blows. The fact that RAAS is also hyper‑active just compounds the issue, making afterload sky‑rocket. 👊🙌 And let's not forget the inflammation‑induced fibrosis that literally stiffens the myocardium. Bottom line: we need a multi‑pronged therapeutic attack, not just a single‑pill fix.

Dorothy Anne

Great rundown! I’d add that a solid exercise plan, even low‑impact like swimming, can improve cardiac output without overloading the joints. Pair that with a Mediterranean‑style diet rich in omega‑3s, and you’ll see both blood pressure and inflammatory markers drop. It’s all about sustainable lifestyle tweaks that add up over time.

Sharon Bruce

Weight loss helps.

True Bryant

Let’s unpack this with some jargon: the maladaptive hypertrophic remodeling in obese patients typifies a transition from concentric to eccentric geometry, driven by chronic volume overload and neurohormonal dysregulation. When you overlay insulin resistance, you get a metabolic substrate shift toward fatty‑acid oxidation, which is metabolically inefficient and produces lipotoxic intermediates. The ensuing myocardial steatosis further impairs contractility. In layman's terms, the heart is trying to run a marathon while carrying a cement truck – it just can’t keep up. Therefore, early pharmacologic RAAS inhibition combined with SGLT2 agents not only reduces preload but also attenuates the adverse remodeling cascade. This underscores the necessity of a proactive, mechanism‑targeted regimen rather than a reactive, symptom‑only approach.

Danielle Greco

Whoa, love the colorful breakdown! 🌈 The part about fatty‑acid oxidation reminded me of a greasy pizza trying to power a race car – it’s just not efficient. Also, kudos for throwing in emojis – they really brighten up the heavy science. If you ever need a meme for the next post, just holler! 😄

Linda van der Weide

I appreciate the thorough overview, especially the emphasis on integrating metabolic panels into routine cardiac assessments. It’s vital that clinicians don’t overlook the subtle signs of insulin resistance when evaluating heart failure risk. The mention of leptin as a contributor to sympathetic overactivity is particularly insightful, as it bridges endocrine and cardiovascular disciplines. Overall, a solid resource for both cardiologists and primary care physicians.

Philippa Berry Smith

While the article is comprehensive, I can’t help but wonder if the pharmaceutical industry is steering the focus toward newer drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors for profit motives. The “obesity paradox” might be a constructed narrative to keep patients on expensive therapies rather than encouraging true lifestyle change. It’s worth staying vigilant about hidden agendas in medical literature.

Joel Ouedraogo

Let’s be clear: the evidence supporting early initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors is compelling, but clinicians must also address the root cause-excess adiposity. Ignoring diet and activity levels while prescribing pricey meds undermines holistic care. A balanced approach that combines pharmacotherapy with structured weight‑loss programs will yield the best outcomes.

Beth Lyon

i think its important 2 note that not evryone can afford bariatric surgery so we need 2 find affordable options like community gym classes and group diet plans they help a lot.

Nondumiso Sotsaka

🌟 Absolutely! Supporting patients with realistic, community‑based programs can make a huge difference. I’ve seen patients turn their health around through local walking clubs and nutrition workshops. Keep championing those accessible solutions!

Ashley Allen

Concise: early screening, lifestyle changes, and appropriate meds save lives.

Brufsky Oxford

Philosophically speaking, the heart embodies the tension between excess and scarcity. When adiposity expands, it tilts the equilibrium toward excess, forcing the myocardium into a perpetual state of over‑work. Yet the paradox lies in how a modest amount of fat can initially buffer stress, only to become the very catalyst for failure. 🤔🙂

Lisa Friedman

People always forget that the renin‑angiotensin system is hyperactive in obesity – that’s why ACE inhibitors are a MUST. Also, if you’re not checking CRP, you’re missing a big piece of the puzzle. Finally, don’t rely on BMI alone; distribution matters more than the number.

cris wasala

Hey everyone, just wanted to say great job on this thread! It’s amazing how many perspectives we’re covering – from the nitty‑gritty science to practical lifestyle tips. Keep the positivity flowing, and remember that every small step counts. Together we can make a real difference in heart health!

Tyler Johnson

When we examine the intersection of adiposity and left ventricular failure, it becomes evident that the pathophysiology is not merely a linear cascade but rather a complex network of interdependent mechanisms that amplify one another in a synergistic fashion. First, the chronic expansion of adipose tissue increases circulating blood volume, imposing a sustained preload that forces the left ventricle to dilate beyond its optimal range. Second, the concomitant rise in peripheral vascular resistance, often mediated by obesity‑related hypertension, elevates afterload, compelling the myocardium to generate higher pressures during systole. Third, neurohormonal activation, particularly the up‑regulation of leptin and the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system, accelerates maladaptive remodeling by promoting hypertrophy and fibrosis. Fourth, systemic inflammation, characterized by elevated cytokines such as TNF‑α and IL‑6, further stiffens the myocardial matrix, reducing compliance and impairing diastolic filling. Moreover, insulin resistance shifts myocardial metabolism toward fatty‑acid oxidation, a less efficient energy pathway that produces toxic intermediates and hampers contractile performance. The convergence of these factors creates a vicious cycle: increased wall stress begets neurohormonal activation, which in turn fuels inflammation and metabolic derangements, perpetuating ventricular dysfunction. Clinically, this manifests as a phenotype of preserved ejection fraction early on, gradually transitioning to reduced ejection fraction as the compensatory mechanisms fail. Therapeutically, a multi‑modal approach is essential; early initiation of RAAS inhibitors, beta‑blockers, and SGLT2 inhibitors can blunt the deleterious cascade, while structured weight‑loss programs address the root cause. Finally, patient education and regular monitoring of biomarkers, echocardiographic parameters, and metabolic indices are indispensable for intercepting disease progression before irreversible remodeling sets in.

Annie Thompson

I find myself reflecting on how society’s relationship with food and body image feeds directly into these heartbreaking medical realities. The relentless marketing of high‑calorie, low‑nutrient products creates an environment where obesity is almost inevitable for many, especially in underserved communities. When those very individuals develop left ventricular failure, it feels like a double tragedy – the body is betrayed by both biology and the socio‑economic structures that dictate daily choices. It’s not just about a heart that can’t pump; it’s about a system that failed to protect the heart in the first place. I’ve seen patients who, despite their best intentions, can’t access safe spaces for exercise or afford fresh produce, and they end up trapped in a cycle of worsening cardiac function. The emotional toll is palpable – anxiety, depression, and a sense of hopelessness that compounds the physiological strain. Yet, there are glimmers of hope: community‑driven initiatives, policy changes like sugar taxes, and the growing awareness among clinicians to address lifestyle factors with empathy rather than judgment. When we combine medical advances with genuine societal commitment, we can begin to untangle this knot. So, let’s keep pushing for both scientific breakthroughs and equitable public health strategies – the heart, after all, is a communal organ.

Parth Gohil

Good point on the need for a jargon‑heavy yet friendly dialogue when discussing cardiac‐metabolic links. In practice, integrating terms like “neurohormonal overdrive” and “adipokine signaling” into patient education can demystify the disease while still sounding professional. Pairing those explanations with actionable steps – such as a 5‑10% weight reduction goal and specific SGLT2 inhibitor benefits – makes the conversation both informative and empowering. Let’s keep the discourse accessible yet technically sound.