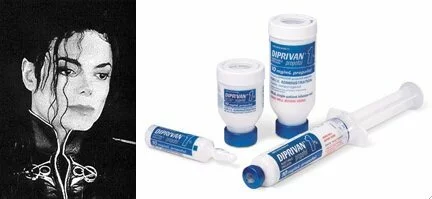

Reports have surfaced that pop superstar Michael Jackson was spending as much as $48,000 per month on prescription drugs, including Demerol and Diprivan.

A sidelight of this story is the pharmacy that news reports say filled and delivered many of those orders: Mickey Fine Pharmacy & Grill in Beverly Hills.

Mickey Fine is a pretty snazzy-looking place. It was originally one of those legendary Schwab Pharmacies where starlets were discovered while drinking milkshakes. As recently as March, it was a featured location in the Starz comedy series “Head Case.”

Mickey Fine is a pretty snazzy-looking place. It was originally one of those legendary Schwab Pharmacies where starlets were discovered while drinking milkshakes. As recently as March, it was a featured location in the Starz comedy series “Head Case.”

It’s not the kind of place you would normally associate with supplying a prescription drug habit.

Let me be clear: there is absolutely no evidence that Mickey Fine has done anything wrong here. But I hope its involvement in the Michael Jackson case will help us to think twice about preconceptions and stereotypes when it comes to prescription drug abuse.

Opponents of American citizens buying drugs from Canada have worked hard to associate online pharmacies with the increase in prescription drug abuse — although there is absolutely not one shred of statistical evidence to support this claim.

The fact is, while it’s certainly possible to use online pharmacies to feed a drug habit, it’s just as easy to borrow medications from friends, sneak them out of your parents’ medicine cabinet — or to get prescriptions from multiple doctors and fill them at a place like Mickey Fine.

On April 30, the secure site for the Virginia Prescription Monitoring Program was hacked and replaced with the following message (expletives deleted):

ATTENTION VIRGINIA

I have your s—! In *my* possession, right now, are 8,257,378 patient records and a total of 35,548,087 prescriptions. Also, I made an encrypted backup and deleted the original. Unfortunately for Virginia, their backups seem to have gone missing, too. Uhoh

For $10 million, I will gladly send along the password. You have 7 days to decide. If by the end of 7 days, you decide not to pony up, I’ll go ahead and put this baby out on the market and accept the highest bid. Now I don’t know what all this s— is worth or who would pay for it, but I’m bettin’ someone will. Hell, if I can’t move the prescription data at the very least I can find a buyer for the personal data (name,age,address,social security #, driver’s license #).

Now I hear tell the F—— Bunch of Idiots ain’t fond of payin out, but I suggest that policy be turned right the f— around. When you boys get your act together, drop me a line at [email protected] and we can discuss the details such as account number, etc.

Until then, have a wonderful day, I know I will

Twelve days later, the site is still down — and the fate of millions of prescription drug records is unknown.

The issue was elevated to Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine late last week. On Thursday, Kaine told the Washington Post that the state will not pay the ransom, and that the FBI and Virginia State Police are investigating the computer attack.

The Virginia Prescription Monitoring Program, launched in 2003, is a state-run database that collects prescription information with the goal of tracking and preventing illegal sales, theft and abuse of controlled substances, such as OxyContin. More than 30 other states have enacted similar programs to tackle the growing problem of prescription drug abuse; it is expected that nearly every state will have such a program soon.

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) says the monitoring programs have been of significant benefit. According to the DEA site:

Prescription drug monitoring programs are being used to deter and identify illegal activity such as prescription forgery, indiscriminate prescribing and “doctor shopping.” Most programs provide patient specific drug information upon request of the patient’s physician or pharmacist. Some state programs proactively notify physicians when their patients are seeing multiple prescribers for the same class of drugs. This assists healthcare professionals in managing patient care. It has been an extremely successful program to thwart diversion in a number of states.

Prescription drug monitoring sites are only accessible — or at least are supposed to only be accessible — to registered healthcare professionals, such as licensed pharmacists.

Computer security experts told ChannelWeb that the hacking underscores the need for better security of online prescription drug records and other sensitive data. The issue is a timely one, as President Obama is pushing to make even more healthcare information accessible online.

Said Paul Ferguson, advanced threat researcher for Trend Micro:

There’s not enough due diligence. There are some very clever and unscrupulous people out there who find ways to get access to this stuff.

We’ve written previously about FDA guidelines for proper disposal of prescription drugs. But with so many discarded medications winding up in landfills and, worse, the water supply, the best solution is no longer flushing drugs or throwing them away. It’s turning them in to prescription drug take-back programs in your community.

The problem, as the Washington Post reports, is that these programs are difficult to set up and maintain — thanks to government restrictions, among other factors.

According to the Post:

In much of the country … drug take-back sites … are almost impossible to find … “We are farther ahead with recycling our garbage than we are with recycling drugs,” said Babs Buchheister, the nursing director of Calvert County.

A major hurdle in any take-back program is what to do with controlled substances — for example, morphine — which constitute about 10 percent of all prescription medications in this country. Under Drug Enforcement Administration rules, a third party — beyond the patient and pharmacist — may not legally have possession of such drugs.

Thus, a family member or caregiver cannot return an unused portion of a controlled substance to a take-back program on the patient’s behalf. And any take-back program must have a DEA-registered representative — a pharmacist or a law enforcement officer — present to accept the drug.

Fortunately, a bill has been introduced in Congress that would make take-back programs easier to create and administer. The Safe Drug Disposal Act, introduced by Rep. James P. Moran Jr. (D-Va.) and co-sponsored by Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Wash.), is designed to encourage state take-back programs. Among its provisions, the bill would permit caregivers to turn over regulated drugs for disposal at DEA-approved, government-run sites.

This legislation is much needed — particularly when you consider that:

- the average American takes more than 12 prescription drugs annually, with more than 3.8 billion prescriptions purchased each year;

- 19 million tons of active pharmaceutical ingredients are dumped into the nation’s waste stream every year; and

- the EPA has identified more than 100 pharmaceuticals and personal-care products in the nation’s drinking water, including antibiotics, steroids, hormones and antidepressants.

We’ve added a button in our blog’s sidebar to show our support for SMARxT DISPOSAL, an initiative by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the pharmaceutical industry to encourage the safe, environmentally responsible disposal of prescription drugs.

We’re hoping that at some point, SMARxT DISPOSAL will add a nationwide list of drug take-back programs to its Web site.

A group of students at California Northstate College of Pharmacy put together this short video on the dangers of sharing prescription drugs like penicillin and Adderall. (Remember, they’re training to be pharmacists — not actors.)

I stumbled across this while reading Gawker: “Teen socialite” Peaches Geldof says the staff at the fashion magazine Nylon prefer prescription drugs over illegal drugs –

What’s the drug of choice at Nylon? “Klonopin.†Peaches was definitely the talky one. Why? “It’s just a very large prescription drug culture.

This confirms our highly anecdotal evidence of Klonopin as a mini-trend for the creative underclass, maybe better than Xanax—not that our shrink is offering to prescribe us any despite repeated inquiries.

Klonopin, classified as a “sedative-hypnotic,” is prescribed for epilepsy, panic and anxiety disorders, restless legs syndrome and other medical conditions. Unfortunately, such drugs are too easily obtained by young people, who often start taking them by raiding their parents’ medicine cabinets.

As Ritch Wagner of Purdue Pharma (OxyContin), who educates medical professionals and law enforcement officials about the dangers of prescription drug abuse, describes the growing problem:

More prescription drugs are creeping up the list of the 20 most widely abused substances, Wagner said, including the painkiller hydrocodone and methadone, a narcotic commonly used to treat heroin addiction that is now used to treat pain.

Abusers are beginning to learn it can “be more advantageous” to use prescription drugs to get high than drugs such as meth, cocaine and heroin. They are easier to obtain, and people think they are safe because doctors prescribe them.

“In my day and age, it was how many of Dad’s beers we can sneak out of the fridge,” Wagner said. “Now, it’s how many pills can I get out of the medicine cabinet.”

Wagner said children are taking whatever pills they can get their hands on, throwing them into a bowl and taking a handful. They’re called punch-bowl or grab-bag parties.

I think what really struck me about these stories was Geldof’s use of the term “prescription drug culture.” I hadn’t heard the term before.

My immediate reaction was to compare it to the “drug culture” of the ’60s and early ’70s, which we relate to young people — specifically, “hippies.” But upon reflection, the “prescription drug culture” isn’t confined to the young in our country today. It’s pervasive.

It starts with the billions of dollars in advertising that pharmaceutical companies spend to get us to stock our medicine cabinets with drugs — drugs that we might or might not really need.

Before the recent advertising campaign, for example, I’m guessing you’d never even heard of restless legs syndrome — let alone gone to the doctor and asked for Klonopin or Mirapex. The medical use of drugs like Xanax and Prozac have gone through the roof among adults of all ages. And don’t you suspect the Viva Viagra! advertising campaign has made Viagra an object of curiosity not only among middle-aged men, but among teenage boys?

When a teenager’s parents, as well as all of his or her friends’ parents, are stocking the medicine cabinet with these drugs, don’t you think what happens next is almost inevitable?

So, how do we solve the problem? Frankly, as I’ve stated here before, I would put an end to direct-to-consumer advertising by pharmaceutical companies.

Others may disagree with this approach, and that’s fine. But however we get there, we need to reach a point where we don’t expect a “pill for every ill.” Because if you believe there’s a pill for every ill, it’s a short step to believe that prescription drugs are the answer for everything — including having a good time at a party.

What could be more symbolic of the growing problem of prescription drug abuse among teenagers than this: a blond-haired, blue-eyed, 16-year-old cheerleader from a Christian high school selling Xanax, hydrocodone, Oxycontin, Demerol, and Percocet to fellow students from the comfort of the BMW her parents bought her?

What could be more symbolic of the growing problem of prescription drug abuse among teenagers than this: a blond-haired, blue-eyed, 16-year-old cheerleader from a Christian high school selling Xanax, hydrocodone, Oxycontin, Demerol, and Percocet to fellow students from the comfort of the BMW her parents bought her?

The girl’s name is Hunter Ashton Johnson. If police allegations are true, it will be interesting to find out where she got her supply; often, it’s from the parents’ medicine cabinet.

Full story here and here.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer posted an article Tuesday night about the longstanding — and arguably worsening — problem of prescription drug abuse among health professionals.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer posted an article Tuesday night about the longstanding — and arguably worsening — problem of prescription drug abuse among health professionals.

The part of the story I found most compelling was the section on D. Christopher Hart, a disgraced pharmacist who has worked hard to redeem himself by educating others. His story:

Hart, 54, lost his Ohio pharmacy license in December 2004, after being caught a second time taking Vicodin from pharmacies where he worked. The first time, in the early ’90s, his license was suspended. He went through treatment and five years of drug testing and AA meetings.

The second time, his license was revoked.

He had been stealing about 15 pills a day, which he said made him feel euphoric, “like a superpharmacist.” He thought he could manage it because he was the drug expert. “Then the disease kicks in, and you have no control,” he said.

Today, Hart lectures on the perils of addiction as an instructor at three Ohio pharmacy schools. He started the class at Ohio Northern University in 2005 with 10 students. Now the class is regularly filled. This fall he added teaching duties at the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Pharmacy in Portage County.

“Somebody in recovery needs to teach this course,” Hart said. “Students want to hear this kind of stuff. The situation is out there. Let’s not stick our heads in the sand.”

As we’ve been writing about here, teens who abuse prescription drugs often get them from their parents’ medicine cabinets. In many cases, the drugs are not currently being used by the parents; they were simply never discarded.

With this in mind, we’ve decided to reprint the federal government’s guidelines for the proper disposal of prescription drugs. They are:

- Take unused, unneeded or expired prescription drugs out of their original containers. Throw the packaging in the trash.

- Mix prescription drugs with an undesirable substance, such as used coffee grounds or kitty litter, and put them in impermeable, non-descript containers, such as empty cans or sealable bags. This will further ensure the drugs are not diverted.

- Flush prescription drugs down the toilet only if the label or accompanying patient information specifically instructs doing so.

- Take advantage of community pharmaceutical takeback programs that allow the public to bring unused drugs to a central location for proper disposal. Some communities have pharmaceutical takeback programs or community solid-waste programs that allow the public to bring unused drugs to a central location for proper disposal. Where these exist, these programs are a good way to dispose of unused pharmaceuticals.

The FDA advises that the following 13 drugs be flushed down the toilet instead of thrown in the trash:

- Actiq (fentanyl citrate)

- Daytrana transdermal patch (methylphenidate)

- Duragesic transdermal system (fentanyl)

- OxyContin tablets (oxycodone)

- Avinza capsules (morphine sulfate)

- Baraclude tablets (entecavir)

- Reyataz capsules (atazanavir sulfate)

- Tequin tablets (gatifloxacin)

- Zerit for oral solution (stavudine)

- Meperidine HCl tablets

- Percocet (oxycodone and acetaminophen)

- Xyrem (sodium oxybate)

- Fentora (fentanyl buccal tablet)

Note: Patients should always refer to printed material accompanying their medication for specific instructions.

The Los Angeles Times reports on the growing problem of teen prescription drug abuse in today’s editions. Although the problem has been tied by some to the rise of Internet pharmacies, research shows that fewer than five percent of teen prescription drug abusers buy drugs from strangers (a category that includes online pharmacies). Most young abusers start in their parents’ medicine cabinet.

The Los Angeles Times reports on the growing problem of teen prescription drug abuse in today’s editions. Although the problem has been tied by some to the rise of Internet pharmacies, research shows that fewer than five percent of teen prescription drug abusers buy drugs from strangers (a category that includes online pharmacies). Most young abusers start in their parents’ medicine cabinet.

An excerpt from the story:

Among teens and young adults 12 to 25, one-third of those who use illicit drugs say they recently have abused prescription drugs — including painkillers, tranquilizers and stimulants. Among kids 12 to 17, 3.3% had abused prescription psychotherapeutic drugs in the last month. Among 17- to 25-year-olds, 6% had abused prescription drugs in the last month…

Studies suggest that for the current generation, as for past drug users, efforts to thwart distribution of some drugs shift thrill-seekers to others that are easier to score — a dynamic that helps explain the move toward prescription drugs…

More than half who reported they had recently taken prescription drugs for nonmedical uses said they got the drugs from a friend or relative for free, and almost 20% got them from a physician. About 1 in 10 who took prescription pain relievers said they bought or stole them from a friend or relative.

Drug enforcement officials have long noted that teens and young adults widely trade, sell and steal stimulant medications, heavily prescribed among student populations to treat symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Fewer than 5% told interviewers that they had had to resort to a drug-dealing stranger to acquire prescription drugs, or even to log onto an Internet site selling prescription drugs.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASA), last week issued a fascinating survey of teens. Two results stood out to me:

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASA), last week issued a fascinating survey of teens. Two results stood out to me:

1. Teens (aged 12 to 17) indicated, for the first time, that it is easier to acquire “prescription drugs such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin or Ritalin, without a prescription” than it is to buy beer.

2. While Internet pharmacies have been widely blamed for the increase in prescription drug abuse, few of the teens surveyed say that the drug abusers acquire their drugs from online pharmacies.

That’s right. Here’s what CASA’s press release says:

When teens who know prescription drug abusers were asked where those kids get their drugs:

- 31 percent said from friends or classmates;

- 34 percent said from home, parents or the medicine cabinet;

- 16 percent said other;

- Nine percent said from a drug dealer

You may recall that just last month, CASA issued a study warning that 85 percent of online pharmacies do not require a prescription. Clearly, the organization is strongly opposed (as we are) to rogue Internet pharmacies.

But I think it’s telling here that — even with all the negative media attention that Internet pharmacies are receiving — these kids didn’t say, “We buy our OxyContin online.” They said they’re sneaking pills from their parents’ medicine cabinets — or their friends’ parents’ medicine cabinets.

This says to me that we need to look beyond the easy scapegoat of Internet pharmacies in getting to the root of the problem of teen prescription drug abuse.

Could it be that the billions of dollars drug companies have spent to advertise, promote and sell their drugs have resulted in a flood of pills on the market?

Could it be that we’re taught by wall-to-wall direct-to-consumer advertising today that there’s “a pill for every ill”?

In this environment, isn’t it reasonable for teens to seek out the much-hyped prescription drugs they keep hearing about?

Let me give you one example. Viagra is a very popular drug among young men, including even teens, who are not impotent but believe that Viagra will improve their sexual performance. Do you think — for even a minute — that Viagra abuse would be as severe if Pfizer had not spent millions of dollars shouting “Viva Viagra” from every rooftop in America?

If you do, you’re kidding yourself. And if you think the problem of teen prescription drug abuse will be solved by focusing on Internet pharmacies rather than the larger issues at work, you’re also kidding yourself.

-

Search Blog Posts

-

-

Trending Content

-

-

Blogroll

- Bullet Wisdom

- Christian Social Network

- DrugWonks.com

- Eye on FDA

- GoozNews

- Health 2.0

- In the Pipeline

- Jesus Christ Our King

- Kevin, M.D.

- Pharm Aid

- Pharma Marketing

- PharmaGossip

- Pharmalot

- San Antonio Asphalt

- San Antonio Life Insurance

- San Antonio Pressure Washing

- The Angry Pharmacist

- The Health Care Blog

- The Peter Rost Blog

- World Vision

-

Tags

big pharma Canadian drugs canadian pharmacies canadian pharmacy consumer reports craig newmark divine healing Drug costs drug prices Drug reimportation eDrugSearch.com FDA Fosamax Generic drugs healing scriptures Health 2.0 healthcare reform Hypertension Jehova Rophe Jesus Christ Lipitor Metformin miracles nabp online pharmacy dictionary online prescriptions osteoporosis peter rost Pharmacies pharmacists pharmacychecker pharmacy spam phrma Prescription drugs prescription medication Proverbs 3:5-8 reimportation relenza Roche saving money SSRI swine flu Tamiflu The Great Physician The Lord our Healer -

Archives

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- June 2011

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

-

Recent Comments

- Ranee on What is the Difference Between Effexor and Cymbalta?

- bAnn805 on Crestor, Lipitor, or Zocor – Which statin is right for you?

- Anna Pham on Why is Medicine Cheaper in Canada?

- Anna Pham on How to Get the Cheapest Prescription Medications

- Anna Pham on How to Travel With Prescription Medication